Let’s start with Kutch. It’s rare to find Sindhi films these days, so I jumped at the chance to host a special screening of the documentary So Heddan So Hoddan made by filmmakers Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar who are also professors at Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. Jointly they have won twenty-nine national and international awards for their films. I’ve been a fan of theirs ever since I saw their film called Our Family that they made, while in Philadelphia. That film dealt with 3 generations of transgendered female subjects who created an alternative family structure, out of choice, in Tamil Nadu.

With So Heddan So Hoddan they explore a different kind of margin. The title literally means “Like Here, Like There” in Sindhi – and the film documents the lives of three cousins of the Sindhi-Kutchi speaking Fakirani jatt tribe from Kutch in Gujarat, who have been brought up on the poetry and philosophy of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai. Bhitai is a medieval Sufi poet, and someone that we Sindhis are especially proud of; we think of him as our very own Rumi and Kabir rolled into one. Bhitai’s poems speak of the pain of parting, of the inevitability of loss and of deep grief. But they are also metaphors for the distance between our inner self and us or us and the divine. Before the Partition the Fakirana jatts, like many other tribes, moved freely across the Rann, between Sindh (now in Pakistan) and Kutch. But after the creation of borders and the subsequent industrialization, the older generation has been struggling to keep alive their pastoral life and Sufi traditions, which celebrates diversity and non-difference, suffering and transcendence, transience and survival.

The film is a reflective poem, saying as much in its silence as it does in its words, conveying more in a single shot of a shepherd or a solitary truck slowly moving across the dessert that many other films convey in their entirety. My highlight is when the wife of one of the interviewees reflects aloud on camera about what the filmmakers will do with the footage. “Will they show this in the cities? Will they be judgmental about our way of life? Why are they interested in us?” she asks.

On one hand, it is sad that like National Geographic documentaries on wild life, we now have to discover our incredible folk culture also through such documentaries and not through real lived interactions. Certainly, the world that So Heddan So Hoddan showcases is fast disappearing. Yet, I’m not worried. Just like the ancient surando instrument featured in the film found itself a custodian and a player in the truck driver Usman Jatt, I somehow feel assured that as long as there are committed film makers like Monteiro and Jayashankar and passionate communities like that of the Fakirana jatts, we won’t lose our heritage. It will live on, in interesting ways.

From the simplicity of Kutch to the cacophony of kitsch! I hosted ‘Kitsch Kitsch Hota Hai’ the opening event of the India Design Week in Mumbai, and what a blast we had! Madhu Jain showed us kitsch film clips from Shree 420 to Himmatwala and held forth on Raja Ravi Verma’s kitsch art and Manish Arora’s clothes. Design thinker Anubha Kakroo from Future Brands gave a fascinating presentation of her research on middle class kitsch – from kitsch homes, to kitsch parties to even kitsch online personnas. While we decided at the end of the event that in India, sub-kitsch chalta hai, we still couldn’t decide on an exact definition of kitsch. Yes, we’re like this only.

Our event kick started the India Design Forum, which in itself was one giant kitsch mela. I was so glad that the mother-daughter duo of Rajshri and Aishwarya Pathy shifted the IDF to Mumbai in their second year. Mazaa aa gaya! What a stellar line up of speakers they managed once again – ranging from design maven Renny Ramekars, the founder of Droog (whose shop I go to almost temple-like each time I visit Amsterdam) to our very own humble-cocky Subodh Gupta who admitted on stage with a cheeky smile that he does commissioned work like the Absolut bottle because, well, they pay him a lot of money for it!

Thomas Heatherwick was brilliant. His radical designs include the Seed Cathedral, the soft movable UK pavilion building that won top prize at Shanghai 2010 expo but what I liked seeing most was the Olympic cauldron from the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony. The cauldron consisted of 204 individual copper plates, one each for each country at the Olympics. The plates came together and were spectacularly lit at the ceremony to create the eventual cauldron. (See the video on Youtube, it is breathtaking when the flames are lit.) Incidentally, Thomas has been working with the Bombay Parsee Panchayat on creating a vulture aviary at Dongerwadi. When that project finally kicks off, I’m sure it will be as innovative as the rest of his work.

“Doesn’t everyone have a yacht?” asked the incomparable Bond-film actress turned interior designer Anouska Hempel while talking about Beluga her own little boat. Anushka travels the world on her mission to create incredibly cool spaces, from the Blake, her first hotel to the eponymous Hempel to the exotic Warapuru spa in the Brazilian rain forest, to equally exotic properties in places like Chile and Lebanon. Underneath the droll humour, there is a keen mind and a commitment to local artisans and crafts. It was a pleasure to hear her speak, just as it was great fun to listen to shoe king Christian Louboutin talk to Vogue’s Bandana Tewari. “How do you keep your ideas afresh,” a young footwear designer asked him. His reply, deadpan: “in the fridge!” Other gems from the Loub included “in case disaster strikes, you won’t be able to run away anywhere in 2 inch heels, so might as well wear 5 inch heels” and “women look sexy naked while only wearing shoes, but not men”.

My favourite IDF speaker had to be Rahul Mehrotra, the Bombay boy turned Harvard don, whose dil is very much Hindustani no matter where he goes in the world. “Bazaar urbanism”, “kucha-pakka” city, the shape-shifting “kinetic city” – his analysis of what makes urban India what it is was spot on. “Not grand vision but grand adjustment,” the kinetic city is about blurring boundaries and co-existence, he added. “Its spectacle is not the architecture of permanence but the festival, temporary in its nature.” For the first time in many years, Rahul spoke about his own body of work. Sharply critical of the architecture of “impatient capital” that created “impractical” and “unsuitable” glass boxes for our cities, he showed us what the alternatives might look like.

These include the headquarters of KMC, an infrastructure company located in Hyderabad. Here Rahul has installed a cooling anodized aluminum skin of trellises (handcrafted, panel by panel, by local craftsmen) over the whole building with flowering plants growing on it. As the building’s water system turns the mist on, the entire building becomes a fragrant, cool and moist vertical park. Rahul’s Dharavi toilet model was extraordinary, with solar panels and a system that made the community have ownership of the toilets, but the city authorities inexplicably scuttled it. “Perhaps it looked too good!” he exclaimed, only half in jest.

Seeing Rahul’s hathi gaon project that is underway in Rajasthan brought tears to my eyes. It is a residential village for 200 mahouts and elephants on the outskirts of the Amber fort in Jaipur, with communal courtyards for families and a pond for elephants to frolic. He has been able to bring about such harmony with very simple, beautiful, locally sensitive architecture. Rahul is seeing the project through despite the several political and infrastructural bottlenecks he is encountering along the way. “This is what maters most,” he said, as he showed us an image of a happy elephant and it mahout bathing in the water. Like with So Heddan So Hoddan, one didn’t need any more words.

I was equally speechless when I popped into Kochi for the closing of the Biennale. What was at the beginning of December, a work in progress, had morphed into a complete viewing spectacle by March. For all those of you who didn’t make it, you really missed something! Wait for two more years now – that is, if Riyas Komu and Bose Krishnamachari have the energy to repeat this again. Bose wore a permanent big smile when I hung out with him in Kochi, so the signs are good.

I close my eyes and am transported back to Moidu’s heritage in Fort Kochi. I am lying down on floor at the Angelica Meisti exhibit. Her “Citizen’s Band” musical videos of ordinary traditional musicians performing in urban environments, are playing on 4 screens surrounding me. Mongolian throat singing and Cameroonian water drumming…the sounds start mingling in the darkness. An azaan call filters in from the mosque next door adding another layer to the work and the experience.

I spend two hours discovering Amar Kanwar’s “Sovereign Forest”. This is a combination of films, handmade books, photographs and exhibits made of grains of rice that together create a complex narrative about farmer suicides, land-grabbing and the systemic enduring violence that ordinary citizens of Odisha have had to live with daily. We are also like this only.

Sunset. A spontaneous sitar and drum jugalbandi is taking place in Aspinwall House near by. Once the summer palace of the Travancore maharaja, this is now owned by DLF and is the main biennale venue. Ferries and naval ships are passing me by on the waterway. Children are soaring into the sky on wooden swings installed on the old gnarled trees in the courtyard. A group of adults climbs up piled up gunny bags to look into Srinivas Prasad’s gigantic bird’s nest installation “Erase” which he plans to burn as soon as the biennale ends.

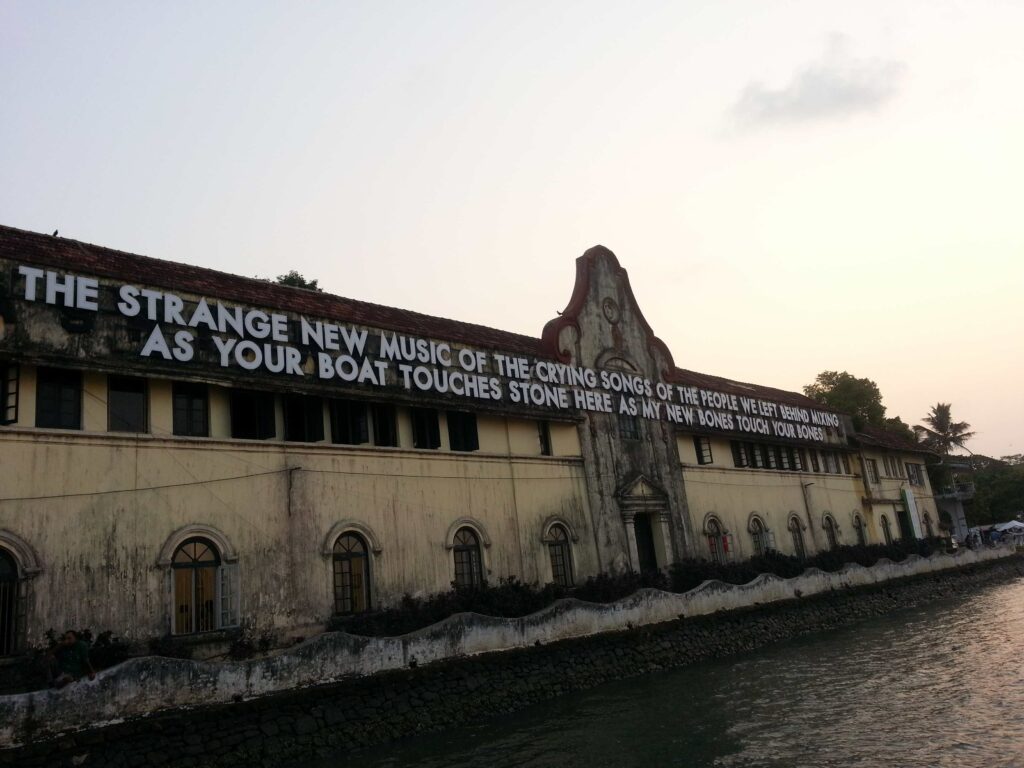

I have just walked past Sheela Gowda and Christoph Storz’s grindstones, smiled at recognizing more than half the people in Atul Dodiya’s art circuit pictures, and gaped at Tallur’s inverted Mangalore tile roofs with their tiny terracotta hatha yogi sculptures attached to them. Then Robert Montgomery’s “strange new music” enters my soul. It plays UBIK’s “Residual Traces”, it plays Alex Mathew’s rusty anchor on the Pepper House lawn, it plays Sudarshan Shetty’s intricately carved sculpture “I know nothing of the end” that is dug into a gigantic pit inside Cabral Yard which once housed Aspinwall’s coir yarn baling press but now lies magnificently, desolately, art filled.

It plays mosquitos and heat and the taste of the open faced savoury cheese tart made from cashew cheese, roasted tomatoes and spinach by Chef Saiju Thomas at the Dutch-influenced East Indies restaurant. It plays mid-evening iced teas at Kashi Café had with the Mumbai art frat one keeps bumping into everywhere in Fort Kochi, like Shireen Gandhy, Deepika Sorabjee, Bina Sarkar Ellias, Mort and Tara. It plays the salt-water spray that hits my face as I hop on to the 2-rupee fifty paise ride across to Ernakulam to see the works at Durbar Hall. It is a music that doesn’t leave me, and I’m all the more richer for this.

I was equally enriched on visiting Startup Village during my time in Kochi. The folks behind Startup Village (it’s a public private partnership between a bunch of national and state government entities and private corporations) want to focus primarily on student start-ups from college campuses, incubate a thousand product start-ups over 10 years and get at least one company worth a billion dollars from among these. It’s an ambitious target but not impossible. Indians make such good entrepreneurs abroad in countries like the US, when there is a favourable ecosystem. Why then do we get bogged down in entrepreneurship when it comes to our own country?

Startup Village aims at selecting potential entrepreneurs with interesting business ideas and then sparing no efforts in scaling these up. Like other global incubators they are providing their would-be entrepreneurs with ridiculously low rents (think one tenth of the rent anywhere else in Kochi), a 4G telecom network, computers, a suite of services including legal and intellectual property advice, and access to potential investors including people like Infosys founder Kris Gopalakrishnan who is their chief mentor. They’ve already got international companies like Blackberry hooked in – when I visited, I spotted a swarm of young men in the Blackberry Rubus Lab creating apps for their new handsets, as well as young teams from companies with names like Cat Media Crew (a cybersecurity startup) and Wow Makers (a design startup).

I also spotted a pallet rack structure right next to the glass and steel Startup Village building that could only be called Jaaga-esque – and when I enquired I realized that it was indeed something that Freeman Murray, the Jaaga founder and an active angel investor in his own right, was building, as a Startup School on site. Kochi is becoming quite the place to be, no? Art on one side, entrepreneurship on the other! Makes me wonder, what am I doing stuck in Mumbai, even if it is very much meri jaan!

* This post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder which appears in Verve magazine every month.