I must say I have really enjoyed this season’s Lakmé Fashion Week (LFW) in Mumbai. For showmanship, it was paisa vasool right from the elegant foreign-return bling of Mumbai’s prodigal son, Naeem Khan (Come on Naeem darling, ghar aaja pardesi, tera des bulaaye, re!) to the OTT dhamaal of Manish Malhotra’s Bollywood brigade (Kajol, Karisma, Hema Malini, Varun Dhawan and Asha Bhosle to top them all, swishing across the ramp to catcalls and whistles). Can any fashion week anywhere else in the world give you so much entertainment, entertainment and entertainment? In terms of a serious fashion progression too, I witnessed enough at LFW and am seeing enough happening elsewhere to make me feel positive about the future of fashion in our country.

There are already many young Indian designers like Rahul Mishra who work with textiles meaningfully. What LFW’s textile day did was to highlight some of the others. My friend Mayank Mansingh Kaul from Delhi curated the exquisite opening show. He assembled three non-mainstream designers who have been working specifically on Indian traditions for a long period of time. First up was Ashdeen Lilaowala, a Parsi gara embroidery expert. Ashdeen has worked with the UNESCO Parzor Foundation as a researcher, documenting the crafts of the Parsi community across the country. At his first-ever Fashion Week show, he displayed modern silhouettes – sexy little black cocktail dresses and thigh-high slit gowns, all embellished with the distinctive white gara motifs like peacocks and butterflies. Very Gossip Girl meets Indian princess. I loved them all.

Gaurav Jai Gupta, who was next, is well-known to fashion insiders. His design studio, Akaaro, creates contemporary Indian hand-woven textiles by mixing age-old weaving techniques with newer materials like stainless steel and Swarovski crystals. Gaurav has created specific limited edition textiles for international labels like Jimmy Choo and showcased at Wills Fashion Week as well as in cities like London. I particularly liked the translucent organza pants and the exquisite sari with distinctive pallus that he showed at LFW, and also the fact that he created some very unique men’s garments, pieces I could covet as well as imagine owning.

My favourite of the three was Swati Kalsi. Swati only creates one-off pieces by private order and does not retail anywhere. Shy and reticent in person, she lets her clothes do the talking for her – and boy, did they speak! She displayed Sujani embroidery that had been created in collaboration with skilled artisans from the Muzaffarpur district in Bihar. Each bold-coloured garment had been painstakingly stitched over months and, while the sewing skill was ancient, the stories the clothes narrated were very contemporary, formed in fractal patterns that you could certainly admire on the runway, but really had to go up close to completely appreciate. Swati’s work is on display in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, and LFW rightfully awarded her their textile heritage award this year.

Now, talking about awards, Ritu Kumar, the grand dame of Indian fashion, was finally awarded the Padmashree by the Indian government this year for her contribution to the fashion industry. It’s a decade too late, if you ask me, but at least they did it! I was invited to moderate the conversation between Ritu, Sangita Kathiwada and Gaurav Mahajan, from Westside-Trent, that kick-started the Indian Textile Day at LFW. It was heartening to note that even though it was 11 a.m. on a weekday, the auditorium was packed – with design students, fashion magazine editors and people from many different walks of life.

Ritu has had an incredible lifetime journey. She began by archiving India’s traditional crafts in post-Independence India under the tutelage of legends like Pupul Jayakar, visiting Indian villages and European museums to connect the dots. Phase two was when she revived traditions like zardozi and created employment for, literally, an entire generation of craftspeople. Then there was phase three, her large-scale retail expansion across the country. When I asked her about her journey she said it involved a small word: ‘confidence’.

“We are one of the few countries that have such a strong textile heritage,” she told me. “Our base is not only hugely historic but it consists of 60 million people who are currently working in the crafts as a means of livelihood. So, our crafts are living crafts; they are not crafts that we have placed in an atelier or in a specialised studio. We have a highly skilled population that is working at the loom or with the printing blocks or other crafts.” Ritu added that the confidence also came from India being a market that could absorb what it produced. Finally, she pointed out, “We have gone through the phase of looking at all the runways of Milan and Paris and the world is creating this hugely euro-centric handwriting.” On the other hand, in India, as Ritu said, “We have created from an indigenous route, our very own fashion handwriting, and this is very rare for a country especially if it’s not hugely supported by the government, like in the case of Japan.”

My second panelist, Sangita Kathiwada, like Ritu, was also used to straddling multiple worlds. As head of the Morarka Foundation, Sangita has supported festivals celebrating India’s North-East as well as the excellent ‘Mantles of Myth’ conference in Jaipur that I immensely enjoyed some years ago. But Sangita is also a retailer, selling designer clothes through her high-end Mumbai store, Melange. I asked Sangita whether her two worlds – intellectual and commercial – ever collapsed into one.

She replied that she did indeed see this crossover happening. She found that clients who came to her store were often very interested in textile traditions. “There are a large number of courses on textile design and art conservation, and we can see more and more people being interested in the tribal heritage of our country,” said Sangita. “Contemporary art collectors in Japan, America and across the world are buying our tribal art, in which our fashion is deeply rooted.” She also gave me an example of how when her foundation screened Susman, Shyam Benegal’s film based on the struggle of rural weavers in Andhra Pradesh in the face of rapid industrialisation, they invited Ramulu, one of the weavers on whose life the film was based, to be present at the screening, along with a loom. This created a huge impact and people not only wanted to see the film again, but also wanted to buy the textiles.

I was pleased to have Gaurav Mahajan from Westside on my panel: in the world of design and even at fashion weeks, commerce is often looked upon as a bad word, and Gaurav batted beautifully for the business of fashion during our chat. I asked him how the new government regulations on FDI in retail would impact the arts and crafts patronage of homegrown brands like Westside. (Trent, the parent company of Westside has also hand-held Zara on their India foray through a joint venture.)

Gaurav’s reply was that the differentiator for homegrown brands like Westside, not just in India but also internationally, will be the ability to tap into what is indigenous. He revealed that the ethnic wear component comprises 30 per cent of the Westside market and contended that this component which includes tapping into indigenous raw materials and arts and crafts, was something that the foreign players would simply not be able to tap in to. Gaurav made me appreciate how the retail economies of scale can create a huge impact for India’s textile heritage, because Westside and other Indian players source, design and produce out of India and not out of factories in China.

Gaurav declared that Westside buys close to 15 million metres of Indian textiles annually, and through this, they are able to thus support scores of villages like Mangalgudi and Hulia. They make sure that this process is profitable and not done as an act of charity because that is the best way to ensure that the crafts and the artisans survive. As a company, they also invest in the infrastructure of the villages they source from, including the creation of water treatment plants and other facilities. This enables the youth to stay back, the same young persons who would have earlier gone to the city and worked as construction workers can now choose to engage with the crafts tradition of the community and keep it alive.

Gaurav shared that Westside had set up centres in cities like Ahmedabad, Jaipur, and Kolkata from which they source fabrics of the region. Westside’s designers worked closely with the fabric sourcing division, the designers spend days at an end in the villages with the master weavers developing the correct design that would be relevant to the Westside consumer. His challenge, he added, was usually that of scale, of continuously getting fabric with consistent quality, but as he said, he and his team were working on this, and innovating together with the village craftspeople.

Innovation is the buzz word, even in the textile space, but there are multiple ways to perceive innovation. As Ritu Kumar herself pointed out during our chat, handicrafts in India are very manoeuvrable and capable of innovation. Embroidery and prints can be put on any kind of fabric including a little black dress. According to Ritu, India’s USP lay in layering of crafts like handloom textiles with embroidery or printing. She made another very valid point when she said that more than the designer-wear, what was moving the Indian market was copies! As she said, when a designer makes a print there are copies of that made available everywhere, and that means that the printing units are thriving, which in turn means the industry is surviving! Plagiarism as a form of innovation and sustainability – now that’s a thought to ponder over.

A lot is indeed happening on the ground with regard to Indian textiles. On the one hand, there is a strong revival movement at the luxury end of the spectrum with established designers like Sabyasachi displaying commitment, and new heroes like Sanjay Garg, whose Raw Mango handloom saris are today as treasured as Birkins among India’s glitterati. On the other hand, as Ritu and Gaurav have shown through their work, there is innovation in the creating scale at the mass level too – and this scale can really change the lives of the artisans involved.

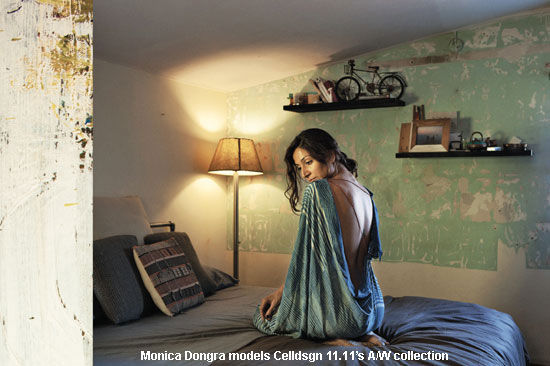

There’s a third kind of innovation happening – this time, on the edge of fashion. Labels like Pero and Shift, run by young designers like Aneeth Arora and Nimish Shah respectively, are being wonderfully innovative by blending western silhouettes with eco-conscious, sustainable, and hand-crafted Indian textiles, and these garments are creating a new sexy look that the country’s hipsters are gravitating towards. Take the case of 11.11, a brand I absolutely love. Longing-belonging, their AW 2013 collection takes its inspiration from tribal costumes all over the world, and uses hand-woven fabrics like khadi merino wool and khadi denim along with techniques like hand block printing, clamp dyeing and felting.

The brand 11.11 is innovative in another way – they are using their lead users, fashion forward people like singer-actor, Monica Dogra, or theatrewallah, Imaad Shah, to pose for, or rather wear their lifestyle in their look books, just as they would do in real life. The new online store Bhane is doing the same – they’ve got uber-blogger Manou to photograph urban hipsters across the country for their new website. Tapping into the aesthetic of the edge, and mainstreaming it is a sound strategy, and since it involves the promotion of indigenous textiles, I like it even more. Yes, a new wind is blowing in the world of Indian textiles and I like how it feels against my skin.

* This post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder which appears in Verve magazine every month.