I recently spent some time with Navi Radjou, Jaideep Prabhu and Simone Ahuja, the authors of the new business book Jugaad Innovation. Jugaad, as you might know, is a Hindi word that can mean different things from a low cost fix that is imperfect but just good enough, to something innovative that comes from being creative, or by using less resources and something that works on improvisation and ingenuity. It has no equivalent word in other languages, although there are some such as DIY (Do It Yourself) in the US, gambiarra (improvisation) in Brazil and zizhuchuangxin (indigineous innovation) in China, which come close.

When I first heard of the book, I must admit I was sceptical. Jugaad is one of those words that have taken off in the past two years in the global lexicon. My non-Indian friends have used it with pride to describe India’s innovation quotient in the past few months and it’s always irritated me, honestly. I used to argue against the glorification of jugaad until I read the book. My rationale then was – why should we think that an attitude of frugality or the ability to do things out of poverty or under desperate constraints as jugaad suggests, as something to be celebrated as a part of our national DNA? Why shouldn’t we create conditions of non-scarcity or non-desperation instead, in our country or in our lives? Why shouldn’t we remove the need for jugaad so that we can innovate on a level playing field with the rest of the world?

I was also piqued because one of the things jugaad also stands for is the delivery of something substandard, or a chalta hai attitude. The origins of the word come from the patched-together truck with water pump engines that many people in north India use for transportation. Fed as we have been in recent years on stories of ‘India Shining’ in international magazines like Business Week and Time, isn’t it perfectly natural to feel indignant that something like this is being used as a showpiece for modern India? (I call it the Slumdog Millionaire effect that many of us urban English speaking privileged Indians are prone to.)

From both these viewpoints, celebrating jugaad the way the Western world has been recently doing seems like a cruel joke. When I actually read the book though, my nerves were soothed, because the authors aren’t glorifying jugaad meaninglessly, or recommending it as an alternative to other kinds of innovation. What they said, both in the book, as well as to me, when we met, is simply that having a jugaad mindset and encouraging it can be a valuable part of a person’s, an organisation’s or even a country’s innovation tool kit. Rather than dismissing jugaad as a poverty-based phenomenon, or being embarrassed of it, we should see how jugaad principles might be formalised and used to spur innovation.

In their reviews, magazines like The Economist have placed the book among the plethora of innovation literature available (this includes the recent book Reverse Innovation, by Govindraj and Trimble, on a similar theme). I, however, see the book as a complement to Banerjee and Duflo’s Poor Economics which tries to understand poverty and adversity, or Sheena Iyengar’s The Art of Choosing, which seeks to find out why some people make certain choices while others don’t. Jugaad Innovation is full of case studies of people and organisations that sought opportunity in adversity, or did more with less, or chose flexibility over rigidity, with powerful results.

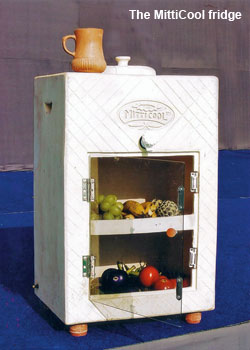

These include individuals like the potter Mansukhbhai Prajapati, the inventor of MittiCool, a Rs. 2000 clay fridge suitable for an India that is off the electricity grid. Mansukhbhai got his idea after the Gujarat earthquake – when he saw a newspaper picture of a clay pot lying amidst rubble, with the caption ‘Poor man’s fridge broken’. That picture inspired Mansukhbhai to create a fridge made out of the material he knew best, clay. The fridge uses no electricity and is 100 per cent biodegradable. After he began to get international acclaim and his order book started filling up, Mansukhbhai started training the other villagers in pottery and devising processes by means of which he could mass produce his products in a factory in his village (he also makes products like non-stick clay frying pans that retain heat longer but cost only Rs 100.)

Sometimes the constraint on innovators is price and is market driven – so Jane Chen, the Stanford-educated head of a company called Embrace, sells low-cost infant warmers for premature babies in India and several emerging markets. Sometimes the constraint is geography. So Dr. Mohan started a Diabetes Tele Medicine clinic to serve rural patients in Tamil Nadu, using vans equipped with testing equipment as well as satellite transmission capabilities so that doctors in Chennai can examine patients remotely and treat them. Sometimes the constraint comes from not having a viable ecosystem for a product or a service, so jugaad innovation comes from creating that ecosystem. So SELCO’s Harish Hande created a model for financing, pricing as well as distributing his solar lantern services in rural, by thinking ecosystem and not just product.

Some jugaad entrepreneurs make their constraints work for them, such as Kanak Das from Morigaon in Assam, who has invented a bike that actually runs faster on our country’s bumpy, crater-filled roads! (A shock absorber fitted on the bike’s front wheel compresses and releases energy into its back wheel as a propulsive force.) Das’ innovation has been patented with the support of India’s National Innovation Foundation, and may soon find its way into automobiles, courtesy a bunch of engineering students at MIT.

Other jugaad innovators serve the margins, or groups that were not previously thought of as viable, and create new markets for these. So a company called Neusoft in China has developed a low cost wristwatch that can monitor a patient’s health and send it to a cloud computing based expert system that can provide solutions and advice. It is becoming a popular gift from young Chinese people to their parents, as the parents’ health reports can be sent to the children on their mobiles, and the children can keep a tab on these regularly.

Jugaad is something that companies from emerging markets have been successful at recently, while expanding into other territories. Mahindra & Mahindra used jugaad to innovate and sell lots of small tractors to American farmers, while China’s Haier has undercut Western companies in many products, from washing machines to wine coolers. Haier has set up effective processes in China where a call is answered within three rings and a technician comes to repair the product in three hours. But at the same time it has also kept enough leeway in their processes and in how they are organised, so that employees can report customer observations from the field, which then help in product development. For example, when its technicians reported that their washing machines were being used to clean vegetables, Haier developed specialised washing machines that could not only wash vegetables, but also peel potatoes.

In response, Western companies are doing their own kind of jugaad, both in their home countries as well as in their operations in emerging markets. Multinationals like GE are taking concepts from the emerging world and using them in the West. GE’s Vscan, a portable ultrasound device, was developed in China and is now sold all over the world. GE also created the MAC 400 in India in 2008, a portable ECG machine that costs one tenth of its Western equivalent. After tasting success in India and China, it has rolled out the product in the US.

Many multinationals are building innovation centres in emerging markets. Pepsico, for example, established the Global Value Innovation Centre in India in 2010 with the aim of finding academics, entrepreneurs and experts who have invented jugaad solutions for making manufacturing and distribution more effective. One of their innovations called direct seeding has already saved them 700 crore litres of water in India, and made them a water-positive company in the country (that is, they return more water to the environment than they consume).

The authors write that jugaad is now something that is being taught in universities. Santa Clara University has a Frugal Innovation Lab. Stanford University has an Entrepreneurial Design for Extreme Affordability programme. Cambridge has an Inclusive Design programme. Even world governments like that of the UK, US and France are embracing jugaad, with a slew of efforts, either online, or through physical contests or challenges, that urge citizens to collaborate and solve real-world issues. Even in India, I believe that Sam Pitroda and the National Innovation Foundation are setting up a US $ 1 billion fund for inclusive innovation within India which will include hard capital as funding as well as soft capital, such as access to networks.

* This post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder which appears in Verve magazine every month.