In this blog post, I want to talk about how we remember the past. Maybe I’m becoming older, in wanting to look back more. I certainly spend my own birthdays in going back to childhood places and remembering how things were, instead of partying mindlessly. I find that it helps to ground me, and give me a sense of perspective.

Looking back as an individual is relatively easy, but as a collective, not so. As a country, we certainly don’t do enough in terms of historicizing the recent past. We talk quite pompously of Indian being a great civilization and having a rich history, but our own knowledge of it is mostly sparse, un-nuanced, and ends with Indian independence. This is unlike countries like the US, to which we fancy comparing ourselves, where every era is richly analyzed from different perspectives to create a complex body of work that serves as a valuable reference for future generations to review, and work from. In India unfortunately, our leaders hardly write memoirs, the history and biography sections of bookstores are relatively sparse, and our archives are not well maintained or given the budgets that they deserve to have. Still, we do manage to produce a decent range of books on Indian history, but the only time they get any national focus is if there’s controversy involved.

So Pulitzer-winner Joseph Lvyeld’s well-researched Great Soul gets a lot of airtime on national and a ban in Gujarat because it ostensibly hints at a gay relationship between Gandhi and a male friend (The book doesn’t actually say this, but no one protesting against the book seems to have actually read it.) Likewise Kuldip Nayar’s recent autobiography Beyond the Lines is creating a furore these days because the veteran journalist has written about former president Zail Singh blessing the formation of the separatist Sikh group Dal Khalsa, something the group’s current head staunchly denies. There have been other incidents such as these, where history books have been reduced to being TV fodder for Arnab and gang to froth over on the 9pm bulletin, and not actual reading material.

To me, this is dangerous. George Santayana wrote that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, and I see this cycle of repetition happening all around us in present times. It is vital that we read about the past widely and furiously; it’s one way that we can ground yourself better in the present.

I would like to recommend three history books that I’ve enjoyed recently. One deals with the history of a country, the second, the history of a city, and the third is the history of a community. (These are not simple distinctions of course – the histories of communities are linked deeply with the history of our country, and the history of our country is as much about cities, states, and geography, as much as about events and the people that shaped them.)

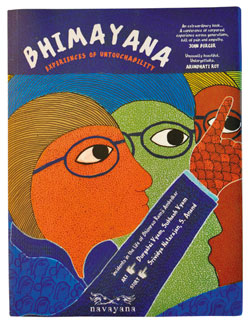

The first book on my list is Bhimayana. This is a richly illustrated rendition of key instances in the lives of Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, who to me has been rather ignored by most of the history books that talk about Indian independence. It’s also strange that when the English-speaking middle classes do talk of Ambedkar, they talk about how he played a key role in drafting the country’s constitution, but ignore his role as a strident campaigner against untouchability and the architect of India’s affirmative action or reservation policies. Even a well intentioned Aamir Khan, in a full one hour long episode on untouchability on his show Satyamev Jayate, chooses to mention Ambedkar only in passing and skips over, or edits out, any mention of reservation for dalits in education or jobs. In contrast, Ambedkar is considered a god-like savior to India’s dalits today, who constitute about 17% of India’s population. Maybe it’s not that strange, because for the English speaking upper middle classes, reservation is a bad word.

This is how Bhimayana begins, then. There is an educated middle class man complaining about quotas for the backward castes to a bespectacled woman. “Well caste is unfair,” she replies simply, and the book takes off. It has three parts, each dealing with a specific instance of discrimination faced by Ambedkar, that shape him into the crusader he eventually becomes. Book 1 called ‘Water’ takes place in 1901 when a young Bhimrao, living in Satara, can’t get a glass of water to quench his thirst, either in school, or in the village, simply because he is untouchable. Book 2 called ‘Shelter’ fast forwards to 1918. Ambedkar has now got a job working for the Maharaja of Baroda who had agreed to pay for his study at Columbia University in New York. But when he reaches Baroda, he simply can’t find a place to stay, however hard he tries. After many hardships, he is forced leave his job and returns to Bombay. Book 3 called ‘Travel’ shift the action to 1934. Ambedkar is now a well known dalit leader but he has an accident when his bullock cart crashes on a village visit. He learns later that the cart’s driver was an untouchable who has never driven it before. The trip organizers had tried in vain to find a professional driver who was willing to drive the famous, but still untouchable Ambedkar around.

The book juxtaposes these relatively simple incidents of discrimination against much more horrific news report from contemporary times. Let us consider just two. On September 29, 2006, in Khairlanji, a small village Maharashtra, four members of a dalit family are attacked and killed in front of forty village residents. The two women are first paraded naked in the village, then raped, then killed. In January 2008, a group of dalits wins their court battle to use a village pond alongside the other residents of the village. But upper caste Hindus take their revenge by directing the village sewer into the pond, thereby ensuring that no one is able to use it.

To its credit, Satyamev Jayate too tried its best to shame its viewers about the India they were living it by disclosing several instances of discrimination such as dalit children being made to sit separately from their classmates, not being allowed to eat the free lunch provided by the school, and being forced to clean all the school bathrooms. However, I found Bhimayana to be a much stronger slap on our collective faces. Sixty years after independence, we have strong laws like the Protection of Civil Rights Act (1955) and the subsequent SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989) that criminalize and punish caste based discrimination, but laws can only do so much in the face of barbaric social practices.

The text in Bhimayana is accompanied by beautiful illustrations by Pardhan Gond tribal artists Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam. They perused the masters of graphic novels in their research – such as Jo Sacco, Art Spiegelman and Osamu Tezuka, and also significant books such as Marjane Satrapi’s Persopolis. In the end they decided to break away from the confines of boxes and instead used the traditional Gond digna home decoration patterns to innovatively curve around and divide the pages of Bhimayana in multiple ways. Gond art signifies rather than represents and the artists have used forms like the fish, the scorpion or birds within the speech or thought bubbles to create a pretty unique illustration grammar that deserves a separate reading just for itself.

One of Ambedkar biggest political fights was with Gandhi, who claimed to be a champion of untouchables in his own way. But Gandhi chose to go on a fast when the British were considering giving untouchables separate electorates and in fact forced the British to abandon this move, writing in a letter to Sir Samuel Hoare, Secretary of state for India, that he wanted to “save them against themselves” by denying them separate electorates. Ambedkar in contrast felt that the internal politics of the Indian independence struggle were horribly skewed towards the upper castes and freedom when it eventually came, would result in freedom for them, but not for the dalits. Bhimayana is a reflection of this sad prophecy, more than six decades later.

The second book I recommend is Ramchandra Guha’s magnum opus, India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. It’s heavy and can cause serious wrist damage, but I found it absolutely riveting and finished it non-stop.

Gandhi only makes a special appearance in the beginning of the book, but the bulk of it is in the detailed history of two very different generations of the Nehru family, Jawaharal and Indira; their differing ideologies, policies and practice of leadership and the impact of these on our country.

Guha is a mesmerizing storyteller and he races through the highlights of post Independent India, including the hastiness with which the British decided to leave, Gandhi’s assassination and the violence of partition. The maneuvering that Nehru had to do as the leader of independent India is well described. I wish some of our current crop of politicians might learn the similar art of consensus building through negotiation. Independent India had several problems and many argumentative factions. Even what language the constitution should be written in was a problem. Nehru negotiated these tricky situations with aplomb and he also managed to eventually get the Hindu code bill passed section by section. Guha also highlights both Nehru’s international prominence as well as subsequent decline; from being a world leader who preached being “nonaligned” to being the head of a country which had lost an embarrassing border war to China. Ultimately, Nehru did the best he could under the circumstances, and he gets high marks from Guha for his integrity and commitment to democratic processes.

Guha is less charitable towards Indira Gandhi, who became prime minister in 1966, less than two years after her father Nehru’s death. Her popularity after the Bangladesh war soared but Guha is critical of how she disbanded democratic institutions to further her own interests. The 1975 emergency in particular is well described, with its illegal arrests and forced sterilizations in the name of population control, supervised by Sanjay Gandhi. He also mulls often in the book on the different separatist struggles, whether in Kashmir, Punjab or the North East, and the ghastly communal riots that keep on occurring every few years with regularity, whether over the Babri Masjid, or Godhra. Keeping a country like India together is a miracle. Overall Guha is hopeful; time and again in the book, he talks about how India as an idea has survived despite its challenges, because of its people, democracy, institutions like the army and IAS, and cultural unifiers like cinema, all of which have shown an impressive and surprising resilience.

Resilience is a term that I would best use to describe Mumbai too. It is a rather new city. The monuments that most people come here to see are film star homes. And Antilla. What we celebrate most here is not our past but our typical Mumbai spirit, our resilience. Princeton professor Gyan Prakash gives this resilience the noir treatment in his book Mumbai Fables. History has never been pacier, or sexier. In fact, for large parts of the book, the threesome of history, geography and biography do a very, very close dance together. It’s hot!

There are nine chapters, each on one aspect of Mumbai’s history. The word ‘fables’ in the title is important. How much of Mumbai’s history is history and how much of it is myth? Prakash, a trained historian, and a self-declared outsider, bites into his sources with relish. Architecture and land records, old Parsi newspapers, comic books, novels, films, music recordings, everything is fair game to mine for stories. Greed and ambition, ambiguity and exploitation, Miranda and Manto – this book made me realize just how vile the city I love and call home is at its core, and how beautiful it is, despite its vileness. I loved the chapter on Rusy Karanjia’s Blitz tabloid and how it covered the sensational Nanavati murder trial of 1959-61, as well as the one on Doga, the Hindi comic-book superhero who as Mumbai ka rakshak (in a dog mask and helped by an army of stray dogs) protects the citizens from evil people, which include terrorists, builders, corrupt cops and politicians. Doga is not originally from Bombay, he originates from the Chambal valley and Gyan reveals that Doga’s creators are outsiders too. The character has been created by a the Delhi-based Raj Comics. There are moments of delightful irony in the book. For instance, the nationalist Khurshed Nariman campaigned hard against the British’s corrupt land reclamation schemes in the 1920s. Then time passed, and the reclamation continued with the same old collusion of politicians and builders in the 1970s. Guess how they decided to honour the fierce opponent of reclamation? By calling the reclaimed land Nariman Point!

There are many, many more books to read once you begin a love affair with history. Delhi Calm, the graphic novel version of the Emergency and William Dalrymple’s The Last Mughal (that traces the last days of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s empire leading up to the 1857 uprising) are two more that I’d suggest. And of course, history need not only be found in books. It has a way of seeping into different cultural forms, even though we may not realize it.

Take the song “I Am A Hunter and She Want to See My Gun” from Gangs of Wasseypur. When I heard it first, it sounded distinctively reggae. This, for a film set in the heartland of Bihar? Given that it was an Anurag Kashyap film, there had to be something more. On scouting around the net, I realized that the song has been partially composed and sung by Trinidad-based Vedesh Sookoo, who is of Indian, and specifically Bihari origin. The British had taken a lot of Biharis to the West Indies to work as indentured slaves on plantations in place of the newly freed African workers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These native Biharis took a lot of their music with them, obviously, music that survived. “I Am a Hunter” is one of these old tunes, which returned more than 150 years later back to India, to the Bihari heartland, via Bollywood, with a reggae/calypso twist to it. Talk about history coming full circle.

I began this blog post by lamenting the lack of enough history accounts being written of modern India. In true Satyamev Jayate style, I want to end on a positive note by praising the work of the Bangalore based New India Foundation (See https://newindiafoundation.org). Funded by Infosys’ Nandan Nilkeni and run by Ramchandra Guha, it gives monetary grants as well as publishing opportunities to scholars who want to write different histories of modern India. We need several more initiatives like these to compensate for the lacuna that exists, but until that happens, hats off to both Guha and Nilkeni for doing what they do.

* This post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder which appears in Verve magazine every month