He explores a Tamil Nadu temple town, and a moving photography festival in Mumbai

As Karthick Iyer and his band appear at the top of the Pushya Mahal Ghat on the banks of River Kaveri in Thiruvaiyaru, a collective roar goes up from the hundreds of girls who gather to watch them, along with a few good men, such as yours truly. Above us, the ghat steps are decorated with hundreds of earthen lamps and fresh flowers, while the sky overhead explodes with fireworks. I look around and everyone in the audience is smiling.

Now, Thiruvaiyaru is usually a pretty sleepy town, located about 15 kilometres away from Thanjavur (formerly Tanjore). It wakes up twice each year. One is for the annual Thyagaraja Aradhana — a festival that has musicians from all over the world coming together for five days each January to sing and pay homage to their patron saint, the celebrated Carnatic music composer Thyagaraja, who attained samadhi here in 1847.

The second time is during the festival of sacred music that I was attending, during which performers like Karthick and others really amp up the excitement among younger audiences, local bureaucracy and administrators of the different venues — all of whom recognise the immense potential of this event to bring global attention and tourism revenues to the town. The residents of Thiruvaiyaru don’t just attend the concerts, but also participate willingly as volunteers, helping to clean up the river bank and other associated venues. It is a collaborative effort that has yielded rich rewards, both commercially as well as in a renewal of pride for their centuries-old heritage.

Post the show, I hang out with festival curator Ranvir Shah from Prakriti Foundation, Chennai. We are at the Diwan Wada, an old Maratha palace that Ranvir has recently acquired and wants to turn into a museum of ancient instruments. The setting is quite trippy, with candles flickering in every compartment of the palace dovecote, and gold-flecked Tanjore paintings elegantly propped up against crumbling walls. Ranvir has his hands full with all the Prakriti events across India. His New Festival is now a major multi-city event hosted by Priya Paul’s Park Hotels chain. Others, like the One Billion Eyes documentary festival and Hamara Shakespeare, have increased Chennai’s cool quotient by a multiple of X.

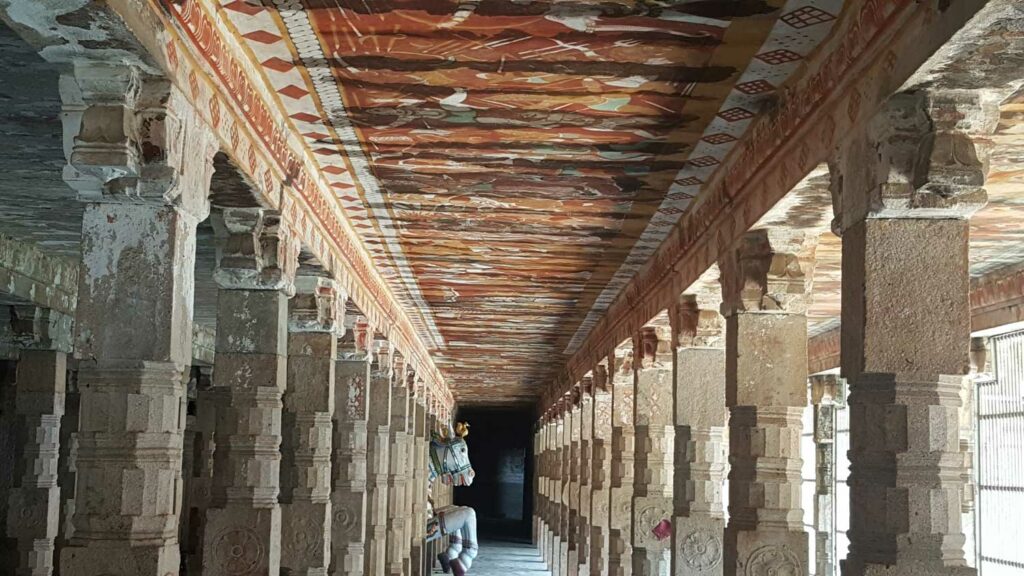

Then there’s all the restoration he’s busy with. The next morning, he takes me to visit the Thyagaraja Temple, spread across 30 acres and built during the reign of the ninth-century Chola dynasty. The Prakriti Foundation and INTACH collaborated for three years to restore the temple’s 17th-century ceiling murals that vividly depict the story of how the image of Lord Thyagaraja Swamy was brought to this location by the monkey-faced king Muchukunda. The murals sparkle in the sunlight as we view them in handheld mirrors. Such imagination and such beauty….

We then drive further to Ranvir’s divine Mangala Heritage homestay that is an hour away. It’s an old-style Tamil Nadu home that he has painstakingly converted into a serene artist retreat in the village of Thirupugalur. “The sacred music festival aims to revive the importance of this region so that we once again reach the glory of how things were during the time of Saint Thyagaraja,” Ranvir tells me as we tuck into a meal on banana leaves in the courtyard. I agree with him wholeheartedly that if done well, in a few years the area can be buzzing in much the same way that Edinburgh or Avignon are during their respective cultural festivals.

The next day, in the middle of a sublime Chitra-Veena recital by N. Ravikiran at the Sri Panchanatheeswara Temple, the evening aarti starts. The maestro immediately stops playing out of respect, and uses the time for an impromptu Q and A session. The music resumes only after the final temple bells have been rung. It is this seamless harmony that I find so lovely. How can one weave something so contemporary as a music festival into the daily fabric of life as it exists, so that there is no friction but a beautiful synthesis?

During my brief stay in Thanjavur, it is a joy to visit the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Brihadeeswarar Temple, one of the fi nest examples of Chola architecture. Nearby, the Thanjavur Royal Palace has so many Chola bronzes that my eyes goggle!

I also realise that Thanjavur and Thiruvaiyaru are luxury destinations just waiting to be discovered. In Thanjavur, I stay at the Svatma hotel — run by the architect and classicially-trained dancer Krithika Subramanian. An excellent spa and restaurant, a pool, hotel rooms fi lled with antiques, a mini veena museum and an outdoor garden cafe that serves wonderful margherita pizzas — what’s not to like? The final touch is when Krithika arranges for the best sari weavers from Thanjavur to visit us at our hotel — I fight over a particularly exquisite black and white silk creation with architect Nondita Correa Mehrotra who, along with husband Rahul, is also visiting the sacred music festival. Who won? I’m not telling! From a fest that was all about rekindling the past, I fl y into Mumbai’s Focus Photography Festival, the theme of which is memory. Founded in 2013 by the trio of Mumbai-based architect Nicola Antaki, photography specialist Matthieu Foss and arts producer Elise Foster Vander Elst, Focus tries hard to extend the medium of photography out of the gallery space and onto the walls of shops, cafes and streets of Mumbai. What do photographs help us remember and how?

This edition of the event — the most ambitious ever — tried to answer this question through its 25 exhibitions and 50 associated events spread across the city — from Byculla and Parel to Colaba. There were so many gems on offer, from Chirodeep Chaudhuri and Jerry Pinto’s tender ode to the discarded books of the People’s Free Reading Room in Mumbai and Shanay Jhaveri’s brilliantly curated William Gedney exhibit at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (formerly the Prince of Wales museum) to Masterji, Maganbhai Patel — an exhibition about a young Indian man (now aged 94) who started shooting his new surroundings after moving to Coventry, England in 1951. Masterji’s restored and curated photographs were shown for the first time in India last month.

My favourite though was the show that curator Prajna Desai had put together at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum on Japanese photography after the recent tsunami and related nuclear disaster there. For those of you who have forgo. en, there was a triple meltdown at the Nuclear Power Plant in Fukushima prefecture in the South Asian country on March 14, 2011 that led to a flight of 1,60,000 citizens from their homes and the creation of a 20-kilometre exclusion zone around the epicentre. Prajna’s exhibition brought together the works of two Japanese artists, Yuki Iwanami and Kota Kishi — both of whom have addressed this disaster through the frameworks of love, architecture and fiction. “What does love look like after the apocalypse? How do the unsung and disenfranchised mark a place? Is recovery at all worth the trouble?” Prajna asked in her note for the exhibition. And there are no easy answers.

I was drawn especially to One Last Hug — Iwanami’s photoessay that staged the lives of three parents across Fukushima and Miyagi prefectures — all of whom are looking for the bodies or personal effects of loved ones that they lost in the disaster, but are constantly thwarted in their search by rules of when and where they can keep on searching. Here’s the story of Kimura, one of the parents, taken from Prajna’s note accompanying the exhibition:

“Norio Kimura was a resident of Ōkuma town in Futaba district, not five kilometres from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Flooded by the tsunami and irradiated, Ōkuma was completely evacuated the morning after the tsunami. Like other affected residents, radiation pouring out of the damaged nuclear power plant compelled Kimura to flee, even though his father, wife, and younger daughter were still missing. By June 2011, Kimura recovered the bodies of his father and wife. Convinced that his daughter’s body is still out there, he continues to look for her, jousting radiation as he goes at it. For two years after 3/11, Kimura was permitted to enter Ōkuma once in three months. In 2015, 30 sessions gave him 150 hours in Okuma per year. Enter and exit. Search and abort. Trauma has a schedule, and a uniform. When in irradiated Ōkuma, Kimura must wear a radiation protection suit.

Long since relocated some 250 kilometres south-west of Fukushima, Kimura lives a quiet life in the pretty mountain village of Hakuba in Nagano prefecture, minimising his reliance on electricity, enjoying low-lit dinners with his surviving daughter, Maiko.”

*This blog post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder

that appears in Verve magazine each month.