This is a post about two biennales that I visited recently. The Kochi Biennale lasted for three months, while the Dharavi Biennale was shorter, lasting just three weeks. But between both of them, they created such incredible energy, and moments of such immense beauty, that I have been left breathless with excitement.

In Kochi, I felt a different energy this time from the first biennale in 2012. Less manic, more contained, inward, and concentrated. Curator Jitish Kallat had invited 94 artists from 30 countries to mull over the theme of ‘whorled explorations’, and their works projected both outward and inward, traversing history and geography, earth and the heavens, at the eight Fort Kochi venues that the biennale was spread over.

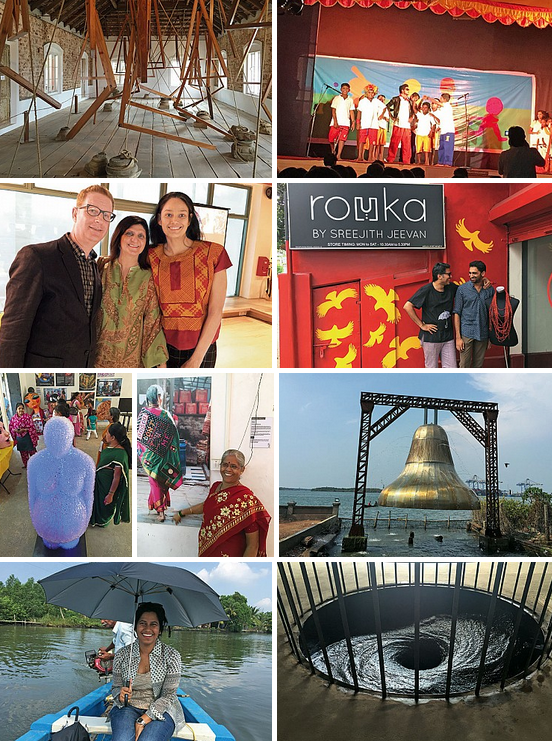

Aspinwall House, the biggest venue, housed most of the superstars this year. Anish Kapoor’s Descension — a powerful caged vortex of water situated right next to the sea — was the star attraction. I’m normally sceptical of much-hyped work, but I must say that Descension did indeed move me very much when I viewed it. At David Hall, the former military quarters, I enjoyed Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pan-anthem, an interactive installation that played the national anthems of different countries while comparing their different levels of military spending.

My favourite biennale venue by far was Pepper House, where I got to witness Three decimal points/Of a minute/Of a second/Of a degree — a sublime Bharti Kher geometric site-specific installation, made even more special by the boat views from the windows in the room that it was located in. I was also moved by Gigi Scaria’sChronicle of the Shores Foretold — a giant 2.5 tonne, 13 feet tall and 16 feet wide bell that seemed to be puncturing both time and history as it stood on the Pepper House shore, in stark contrast to the giant cranes at the container terminal located on the island right opposite. This perforated bell was installed on the eve of the biennale by individuals from the Mappila Khalasi community from Kozhikode, in an evocative performance.

One of my favourite biennale memories is of sipping mint lemonade at the Pepper House café, while nibbling on their divine carrot cake, and making new friends by chatting with those at the table next to me. Pepper House’s owners, Isaac and Tinky, have spent the past few years in refurbishing it as a labour of love. During non-biennale season, the venue functions as an art residency — and they have also opened within their premises, one of India’s most exciting stores dedicated to contemporary Indian design. It is stocked with clothes by Pero, furniture by Design Temple and Lekha Washington, bric-a-bracs from Locopoco, bow ties by Torts, their own range of Kerala spices, and books, glorious books — I spent a large amount of my time (and money!) there.

There’s a lot of good design in Kochi, I must say. I spent half a day at the atelier of one of my favourite designers — Sreejith Jeevan. He is moving his Rouka brand into many exciting directions. A beautiful discovery for me during this trip was Kayal, which is a very private exclusive resort on a small backwater island, far away from civilisation. Maneesha Panicker, the owner of Kayal, quit her comfy job with Estee Lauder in New York some years ago to start Silk Route Escapes, a luxury travel consultancy. Kayal is her new project — an ultra exclusive experience with just two cottages, located on Kakkathuruthu, or the island of crows. Kayal is only connected to the mainland by water, and so to build the resort, they had to cart everything across by boat, even during the monsoons.

Each aspect of Kayal was so personal and so intimate. The wonderful cottage bedrooms, the open air bathrooms, the beautiful lounging areas, the private boats and the home-cooked exquisite meals — this is the new face of luxury, deep intimate and meaningful. I picked up a book while there and started reading. “Why do you stay in prison, when the door is so wide open?” Rumi asked from the random page I had opened, and I couldn’t agree more.

I landed back in Mumbai refreshed, and right in the midst of another biennale! Organised by the non-profit SNEHA (Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action), the second Dharavi Biennale was wonderfully collaborative. The curators, David Osrin and Nayreen Daruwalla, had invited artists of all kinds, scientists and activists, to work with the residents of Dharavi and develop locally resonant artworks around the theme of urban health. They conducted workshops over a period of two years to develop these art projects, and what I witnessed during my visit was an explosion of creativity. Art through performances, art through workshops, art as film screenings or theatre — take your pick.

I had a great time attending Ishqiya Dharavi Eshtyle — Paromita Vohra’s play that was directed by Latesh Poojary and featured Dharavi children between the ages of 5-15. It was a simple love story between a boy and a girl, interspersed with lessons on sanitation and religious tolerance, as well as songs including Jumma Chumma, that had me dancing in my seat. The Healers of Dharavi — an exhibition of portraits created by Dharavi’s signboard painters — honoured the neighbourhood’s local heroes such as Dr Chang, a dentist who has practised in the neighbourhood for 35 years, charging minimal fees. Other healers featured there include bone-setters, homeopaths and acupressurists.

A major theme of the biennale was gender — many of the art works and installations focussed on women’s issues. Intercutting through these was the theme of sustainability —so a lot of the work consisted of recycled materials. I was awestruck by a sculpture, made by Vandana Kori entirely out of 70,000 used injection syringe bottles, in the shape of a pregnant woman. The ‘safety deposit boxes’ was another beautiful project — for this, Dharavi’s residents had imagined their ideal safe spaces as tableaus incased inside small acrylic boxes.

I was proud to host one of the Dharavi Biennale’s opening events at our Godrej India Culture Lab in Mumbai. Art historian Prajna Desai, had envisaged her Dharavi Food Project as a workshop that explored two ideas — food as art and women as aesthetic producers and creators in the food making process. She spent several months in Dharavi, working with the residents, talking to them about their relationship with food, and cooking together with them. The book that has emerged from this project, The Indecisive Chicken, should be released soon.

*This blog post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder that appears in Verve magazine each month.