I have enjoyed collaborating with Lakmé Fashion Week for the past two seasons. For Autumn/Festive 2013, I brainstormed with Saket, Asha and Gautam from the organisers IMG Reliance to see how we could create an intellectual discourse around fashion at the event and engage a wider audience in the city. Ultimately we decided to conduct a pop-up version of the Friday Funda discussions that I regularly organise at the Godrej India Culture Lab, right into the middle of the LFW Talent Box.

My friends at the artist collective, Visual Disobedience, including artist-dancer Amrita Bagchi, had created a beautiful mural that served as a backdrop to the Funda. We had a housefull audience, with people sitting on the floor. More importantly, since we opened up attendance to the entire city of Mumbai, it was a chance to democratise Fashion Week beyond the small coterie of regular insiders. In fact, the best questions came from these ‘outsiders’ – whether about fast fashion, handicrafts, Indian fashion’s environmental friendliness and more.

Predominantly I wanted to explore how fashion translates itself from the runway to the wardrobe to the street to the digital domain. For this, I’d invited Bandana Tewari, Tina Tahiliani-Parikh from Ensemble, Malika V Kashyap from Border&Fall, Anirban Mukherjee from Future brands and Edward Lalrempuia from Pernia’s Pop-Up Shop, to participate.

Tina provided a nostalgic master class on the history of Indian fashion through the story of Ensemble, early designers like Rohit Khosla and the memories of her first Ensemble show in 1988 held in the ballroom of The Taj. “The lights dimmed, Philip Glass music played and supermodel Shyamolie Verma came on,” she reminisced. As Tina noted, fashion then had dynamism and enormous energy. “Each piece was a labour of love for the designer.” But customers were tentative; they were used to buying Indian legacy crafts such as Benarasi saris or jamevar shawls, but would go to their darzi to stitch a salwar kurta or otherwise, shop abroad. “A lot of Ensemble’s work was in educating the customers.” She remembered how there would be a big Ensemble show every year in October that would feature 10 or 12 designers and how they would spend months in preparing for it.

Then the changes took place rapidly. NIFT opened, Fashion Weeks began, and more designers came into the fray, and faced with orders, numbers and sizes, they become more commercial. The India prosperity story kicked in. Fashion magazines – both local and international entered. Page 3 supplements were launched by newspapers and Bollywood and TV shows crept in to influence customers. High Street brands like Mango and Zara entered India and compelled western wear designers to shift toward Indian styles and bridal wear, “as they realised this is where India loosens the purse strings.”

In today’s India, Tina finds a wide spectrum of customers, ranging from “new money, that is willing to buy anything, for whom the frame of reference is very different” to “customers who have gone the full cycle, and who now want something special and not yet another anarkali.” She revealed that Ensemble’s new strategy is about returning to its core. “What did we stand for, what do we stand for today and how to keep that specialness in our vision, products and retail.” She also stated that Ensemble was passionate about reviving the sari.

In contrast, Mallika V Kashyap felt that the sari was waning. She found people wearing saris only as occasion wear, and noticed a clear shift away from traditional Indian clothing in her wardrobe explorations for her website. “However, crafts are not dead. Instead, they are, consciously or unconsciously, being incorporated into people’s wardrobes – whether in people getting their clothes stitched, or wearing bandhni T-shirts.” Mallika added that while “people are either creatures of comfort or creatures of habit” they also have certain garments that they hold on to that form the “influencers” category in their minds. These might be heirlooms that have been handed down or garments that they have purchased from a certain trip somewhere that may not be their style entirely. So there is definitely a clear line between what they wear and what they derive influence or inspiration from.

Anirban Mukherjee from Future brands shared three experiences about people using fashion to make meaning in their lives in the smaller towns in which he conducts his research. In Salem, during a conversation with three young gentlemen, he learnt of the notion of ‘MNC formal’ (long sleeves shirt, trousers, polished shoes) versus ‘local formal’ (jeans, shirt with short sleeves). The sanctity of formal clothes was being subverted. “People are not conforming to standards but just pretending to conform.”

In Bareilly, Anirban visited a market place where he chanced upon a version of suit that had a tie and jacket stitched on to a shirt, all in the same colour. In a way it was a mockery of the suit. But as Anirban said, “The outfit raises the question about why do we need a suit and if there is a need for the suit then let us do what we want to do with it! This is what happens to the street.”

Anirban’s third story was from Number 10 Market in Bhopal where he met a boy with skinny black jeans and long black hair. When Anirban asked him if he could take his picture, the boy went and spiked his hair and said, “This is my emo look.” The boy had downloaded Japanese images of emo styles on his phone. While he did not know the cultural context of emo style, he had short circuited the entire process of growing up in that kind of culture, or its music or aesthetic via his cellphone and adopted it for himself. Listening to Anirban I was reminded of my MIT professor Henry Jenkins and his notion of ‘pop cosmopolitanism’ – how in today’s world – the media is enabling people to engage with lifestyles very far from their geographical orientation.

Through his observations, two aspects of Indian fashion have emerged for Anirban. The first is that fashion is a response to the changing institutional architecture in small town India. “Patriarchy or place of work – every time something changes, there is a dialogue there is a playfulness that takes place and the individual expresses this new relationship through fashion.” Secondly, as Anirban noted, “fashion is about accessing a powerful vocabulary about yourself” and while mainstream fashion events like LFW are building certain firewalls around fashion because of their elite nature, on the street, a new vocabulary is being produced constantly (jodhpurs being called balloons; the evolution of shurtis – the marriage between the shirt and kurti). I couldn’t agree more.

Bandana Tewari spoke about a topic close to my heart – about the relevance of fashion magazines in today’s world and the need to metamorphose them into the online domain. Her former colleague

Edward Lalrempuia who has made a successful shift online, shared his experiences about this transition. Working as a stylist, Edward realised that very often, the styles were forgotten by the time they were seen in the magazine. “But now, people are accessing trends immediately after they are showcased.” The e-tailer he now works with, Pernia’s Pop-Up Shop, had started selling collections of some Lakme Fashion Week designers right after their shows ended. “On a website you know immediately if you’re a success or a failure as people are responding immediately,” said Edward. Another insight that he shared was that his customers wanted to buy “looks” exactly as they see them on the ramp and not trickled down versions.

These conversations really charged me up. As Bandana asked in the context of Anirban’s Bhopal narrative, “What is a Harajuku girl? That image is created through magazines, through the Internet – but it is adopted and assimilated globally today.” Some weeks later, a brown Miss America Nina Davuluri gets crowned. But what does it mean to be an Indian-American Miss America I wonder. Does it mean showcasing your American-ness through evidence of your assimilation or your Indian-ness by doing a Bollywood number? And when a Miss America uses ‘Bollywood dance’ to win a pageant – does the dance then become an American cultural act?

Media and pop cosmopolitanism are subverting all preconceived notions of identity and culture and people are creating composites of themselves. In the same way that Mallika’s interviewees are mixing and matching their wardrobes, in the same way that Tina’s buyers want the mainstream as well as the meticulous, in the same way that Edward’s online shoppers want the exact look from the ramp to wear in their small-town parties, there is a mix and match modernity story being played out in India and across the world and it is fascinating to watch it unfold.

I don’t know whether it is the times we live in – with women’s issues like rape on the front page of our newspapers each day – but this time I read the entire week, through the lens of gender. My highlights included Little Shilpa. Her collection ‘Grey Matter’ had silk saris worn with men’s shirts, T-shirts or katori choli-shirts. Her head and face Perspex and Plexiglas ornaments turned the models into gender-bending deities – and it was a pleasure to see stylist-turned-designer Nikhil D (I love his capsule collection currently showcased in Delhi’s Grey Garden), walk the ramp for Shilpa in his chic bearded, skirted avatar.

In contrast to woman as goddess Sneha Arora showcased her woman as a warrior wearing military prints and abstracted camouflage dresses with words like ‘courage’ stitched on to them. I have always liked Sneha’s meticulousness and this time too, the attention she paid to detail – not just in her show – but also in the way she personally decorated her stall, by splashing tea on to the side panels to get just the effect she wanted – was a pleasure to behold. Amit Agarwal’s woman in striking contrast was Blade Runner-esque and futuristically fierce, while Payal Khandwala’s woman reinterpreted the sari, using special woven fabrics and edgy silhouettes to do the talking.

Women took centrestage as performers too. Sona Mohapatra’s feisty feminist singing for Anita Dongre and Rachel Varghese belting out the blues for Sabya captivated me. Seeing Sabya’s modern maharanis at the grand finale, in their ’20s Chanel-style horizontal striped T-shirt blouses, luxurious embellished saris and sunglasses, I was transported to fantasy-land. This was fashion as escape, as a dream, and a very different take from, say, a Sneha, which was about fashion as a lens to view current times, but that is what makes a Fashion Week so exciting – reality and dreams coexisting; like mirrors and smoke.

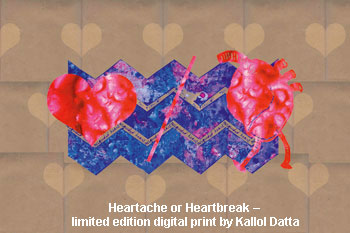

I also like the new direction that designers like Kallol Datta are taking off the ramp. Kallol started doing his iconic prints years ago – and this season while everyone from newbies Quirkbox and Ragini Ahuja, to established names like Masaba and Nikhil Thampi created their own iconic prints – Kallol decided to shift his prints off clothes and on to walls. From observing Kallol as a resident at Khoj’s fashion and art workshop some years ago, to his display last season of his clothes at Mumbai’s Project 88 (he showed before that at the Harrington Street Arts Centre in Kolkata), I have thoroughly enjoyed his progression as an artist. His digital prints were exhibited at Delhi’s United Art Fair this month and are as quirky as his clothes. Since it is Kallol, they question notions of gender and propriety in his trademark ironic style.

*This blog post is a modified version of my column ‘Parmesh’s Viewfinder’ which appears in Verve magazine every month.