Each August, as our country celebrates yet another Independence Day, I try and find alternative ways of remembering the past. The history of our textbooks is one thing; the ordinary history that we tell ourselves is another. There are many ways of remembering and of preserving the past and I want to share some of these with you in this blog post.

Vidyun Sabhaney, the Delhi-based comic book writer, used her grant from the Indian Foundation for the Arts (check the IFA out online – https://www.indiaifa.org/ – they’re doing some incredible work) in 2012 to document three traditional Indian storytelling forms that combined oral traditions and the visual arts. The forms chosen were Karnataka’s Togalu Gombeyatta (leather puppets), Bengali Pat (scroll) painting and performance, and Rajasthani Kaavad (story cabinets).

During the course of her study, Vidyun found that in a bid to remain relevant, each of the traditional storytelling forms was adapting to our changing times in its own unique way. For example, Pat painters now incorporate modern elements like the Asian Tsunami or 9/11 into their works in an effort to attract the tourist markets. Similarly, in the case of Kaavad, the traditional version is about one-and-a-half feet tall. But because tourists need smaller versions that they can pack into suitcases, these are now being made, some as small as three inches. On the other hand the craftsmen are also making larger Kaavads that can be viewed in museums. When I met Vidyun in Mumbai, she told me about how hospitable the traditional artists that she visited were – they really wanted people to visit them and document their traditions and were acutely conscious of the need for preservation. Vidyun and her collaborator on the project, the Japanese manga artist, Shohei Emura, further decided to document their journey of encounters with these visual storytelling masters of our country in a comic book – thereby creating another layer of visual documentation, another alternative archive for the future.

My friend, Tara Deshpande, has also been busy in preserving history in a different manner – through the lens of food. Tara was always ahead of her time. She became a MTV VJ in the early days of the channel. She published her first book of fiction and poetry at age 23 with HarperCollins, and acted in Indie films way before it became cool to do so, like two of my favourites – Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin and Bombay Boys. She also had a parallel stage career that included playing the lead in Alyque Padamsee’s Begum Sumroo.

I first met Tara in 2001, when she was writing The Motive, India’s first Internet novel. She wrote a first chapter, invited readers to suggest a second, then wrote the third and so on until the book was completed. It was the early days of the Internet, ripe with possibilities, when participatory media, fan fiction, and other such genres were still evolving. Then, Tara got married and suddenly disappeared from the scene. Just like that.

When I reconnected with her years later in Boston, she was a celebrity in a very different space – food. She was running a successful catering company and teaching. I realised that this was yet another side to her, a side that had studied at the French Culinary Institute in New York and at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, a side that was researching food and its history and had even done a cooking show on PBS television in the States.

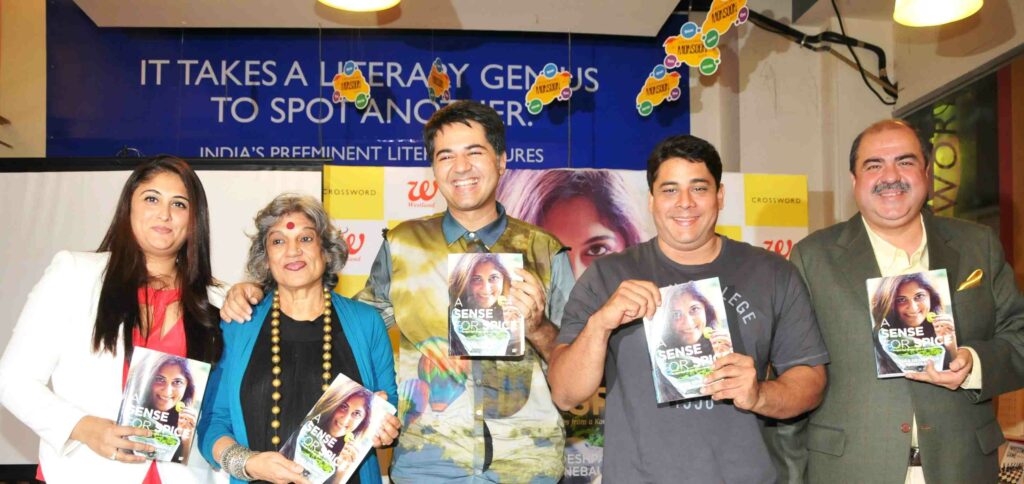

This hybridity, this layering of experiences on top of each other – palimpsest like – is what makes Tara so special, and I have seen that in her work, whether as a performer, a writer, as a chef or now, as a food historian, with her new book A Sense of Spice, that she invited me to help launch in Mumbai. Part cookbook, part memoir, it is full of recipes, with stories attached to them. While reading it I learnt about the history of the Konkan region and many simple things, like the difference between Dharwad and Karwar, for instance. But what I treasure most in the book are the memories that she draws upon.

Like that of her grandfather and his old, reliable Ambassador car waiting for her and her sister to arrive from the city on a Belgaum bus, wearing one of three shirts he possessed – or of her grandmother waking up at the crack of dawn and slaving over food in the kitchen from morning to night. In Tara’s book, she looks at food as celebration, food as love, food as bondage, food as choice, food as history and, above all, food as memory.

I was especially moved because Tara had brought her grandmother with her for the reading. Having lost my own grandmother only a few days before, seeing Tara interact with her grandmother opened a floodgate of memories. Of pigeons being fed each evening. Of orange ice lollies, had with big bowls below, to prevent dripping. Of bell-bottoms and school bus journeys. Of blessings during exam time. Of love, pure, simple, unadulterated. I was numb at the funeral, but on reading the evocative passages from Tara’s book, my eyes filled up with tears.

Food might be one way, but fiction is another, of looking at history differently. We are the stories we tell ourselves. How can we write the stories of our past differently? There has been a new wave of historical fiction writing globally, whether it is Hilary Mantel or Dan Brown. Indu Sundaresan has kept the Indian flag flying in this genre for more than 15 years now with her fictional feminist trilogy of the Mughal Empire. Her trilogy, which comprises The Twentieth Wife, The Feast of Roses and The Shadow Princess, is rich in details of royal darbars, imperial gardens, magnificent palaces and the the cut-throat politics that take place between the palace inhabitants. The first two novels describe the love story of Emperor Jahangir and the daughter of a Persian nobleman, Mehrunissa, who after marrying Jahangir becomes Empress Nur Jahan – his 20th wife. The third book is about Nur Jahan’s grand-niece, Jahanara, Shah Jahan’s daughter.

I chatted with Indu at Pop Up INK – a mini version of the INK conference that I co-hosted with the INK founder, Lakshmi Pratury, at the Godrej India Culture Lab. She spoke about how Nur Jahan not only captivated Emperor Jahangir, but also exerted her authority over the Mughal Empire. Even though she lived in the 17th century in a harem, and wore a veil, she was ambitious and powerful and used her power well. Jahangir married her when he was 42 and she was 34. Between 1611 and 1628, until he died, she ruled the roost. She signed her name on royal documents, had a seal made with her name, and even had coins minted with her name. However all the official histories of the period don’t really tell us much about the lives of women – Nur Jahan or Jahanara, or for that matter, Mumtaz Mahal. This is why Sundaresan’s historical fiction is important. Meticulously researched, it provides an alternative way of looking at the past, albeit with the masala that fiction enables.

But not all history can be fictionalised. Our country’s recent history, often violent and frequently disturbing, tends to get distorted in the spin machine of the nightly news-hour. Take Gujarat for instance. Through oral history and art, the memories of the post Godhra riots of a decade ago are being kept alive by the efforts of artists like Vasudha Thozur and her exhibition Beyond Pain: An Afterlife, which, in Mumbai, took place at both Sakshi and Project 88. The exhibition features artworks created by artist, Vasudha Tozhur alongside the works of six young girls who lost several family members during the riots. Thozhur collaborated with the feminist writer, Bina Srinivasan, and the organisation, Himmat, a collective composed of riot-affected women from Naroda Patiya, and worked with the young girls for a period of ten years, teaching them embroidery, painting, photography and collage-making.

In this context, I am also happy to share the work of Jeff Roy. He is one of four American Fulbright-MTVU programme awardees this year who are working on projects that extensively explore the use of music as a base of mutual understanding between global cultures. Over the past year, he has been based in Mumbai and working on his documentary about how music and dance within Mumbai’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and hijra communities, help to empower and strengthen their individual and collective voices.

It was my pleasure to host a special screening of his documentary in progress just before he left India. From Prince Manvendra Singh Gohil, the master classical harmonium player and esteemed activist who organises concerts in his Rajpipla Palace, to the Dancing Queens, a not-for-profit dance troupe that mostly comprises hijras and kothis, to the Queer Flash Mob that took place at last year’s Mumbai Queer Pride parade and more – Jeff has documented it all. This film will serve as an important addition to India’s queer history archive once it is completed. The recent US Supreme Court decision, granting marriage right to all American citizens, irrespective of their sexual orientation, is historical. For us in India, for now, we have a historic 2009 Delhi High Court verdict that decriminalises homosexuality but an appeal made against this verdict has reached the Supreme Court. Marriage rights are still a long way off. But, as we embark on the long certain road to equality, it is important to document the process. Because what happens today will be history tomorrow.

* This blog post is a modified version of my column Parmesh’s Viewfinder that appears monthly in Verve magazine.